Unearthed

The Landscapes of Hargreaves Associates

Karen M'Closkey

University of Pennsylvania Press | 2013

Winner of the 2014 J. B. Jackson Book Prize from the Foundation for Landscape Studies

“M’Closkey avoids the spurious dichotomies of design versus planning or art versus science, recognizing the complexity and ambiguity in Hargreaves’ work. Original and thoughtful, Unearthed places designed landscapes in the context of theory, legal and economic issues, and the changing morphology of cities.”

Kenneth Helphand, University of Oregon

“Unearthed redresses the paucity of scholarship about Hargreaves Associates through a grounded, sustained treatment. A valuable contribution to studies of contemporary landscape architecture.”

David L. Hays, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

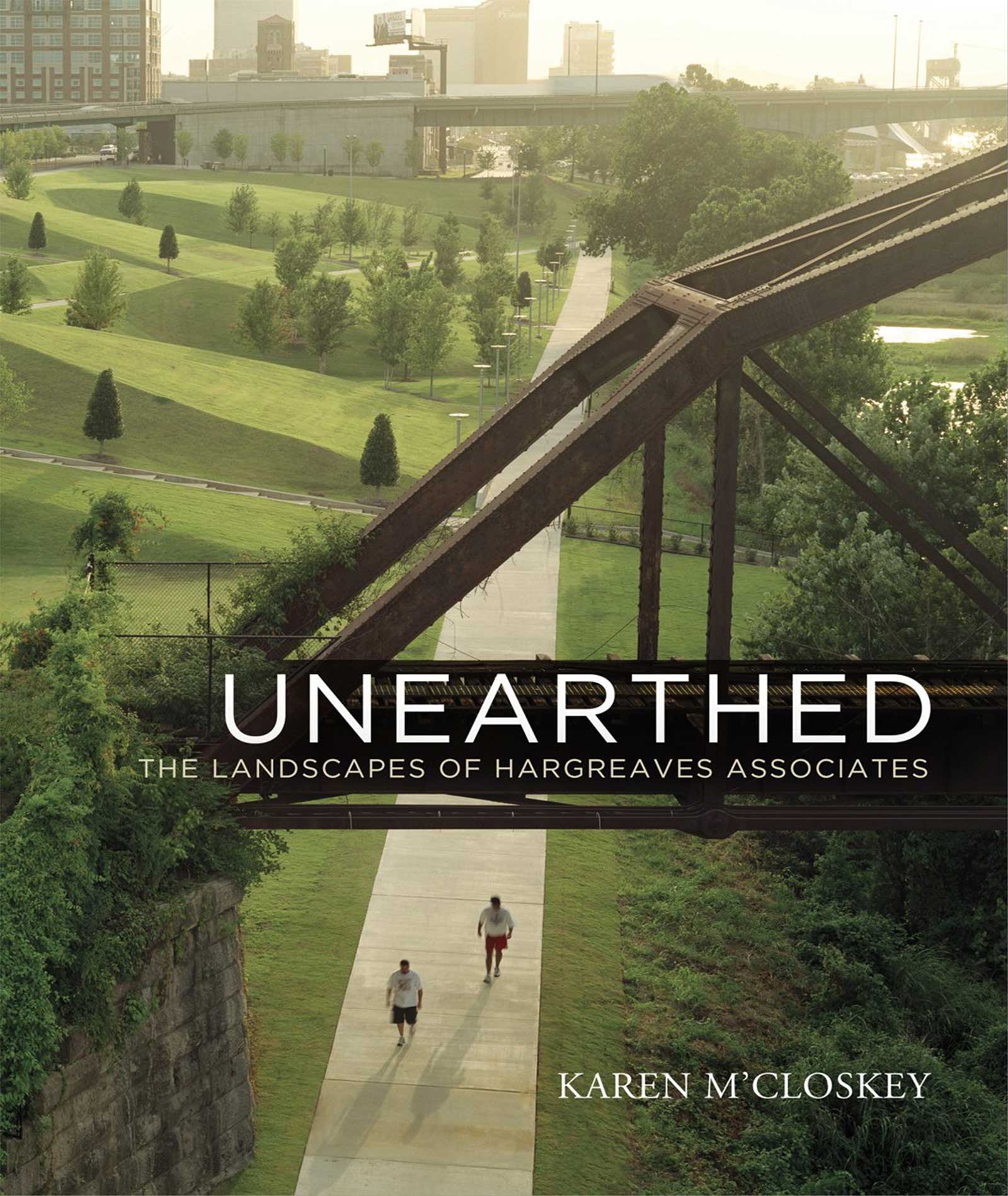

The work of landscape architecture firm Hargreaves Associates is globally renowned, from the 21st Century Waterfront in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to London’s 2012 Olympic Park. Founded by George Hargreaves in 1983, this team of designers has transformed numerous abandoned sites into topographically and functionally diverse landscapes. Hargreaves Associates’ body of work reflects the socioeconomic and legislative changes that have impacted landscape architecture over the past three decades, particularly the availability of former industrial sites and their subsequent redevelopment into parks. The firm’s longstanding interest in such projects brings it into frequent contact with the communities and local authorities who use and live in these built environments, which tend to be contested grounds owing to the conflicting claims of the populations and municipalities that use and manage them. As microcosms of contemporary political, social, and economic terrains, these designed spaces signify larger issues in urban redevelopment and landscape design.

The first scholarly examination of the firm’s philosophy and body of work, Unearthed uses Hargreaves Associates’ portfolio to illustrate the key challenges and opportunities of designing today’s public spaces. Illustrated with more than one hundred and fifty color and black-and-white images, this study explores the methods behind canonical Hargreaves Associates sites, such as San Francisco’s Crissy Field, Sydney Olympic Park, and the Louisville Waterfront Park. M’Closkey outlines how Hargreaves and his longtime associate Mary Margaret Jones approach the design of public places—conceptually, materially, and formally—on sites that require significant remaking in order to support a greater range of ecological and social needs.

University of Pennsylvania Press

Preface

The increasing prominence of landscape architecture over the past two decades is undeniable, due in no small part to the widespread attention to issues of sustainability and the sense of urgency that accompanies our current environmental problems, which are now understood in a global context. Landscape’s centrality to addressing these issues – the form of future urban settlement, and the importance of ecological and recreational networks to guide such settlement – is becoming more apparent to those outside of the field, which has helped reestablish landscape architecture in the significant position it previously and deservedly enjoyed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, such increased visibility of the discipline has been accompanied by a narrowing comprehension of its full cultural efficacy, due to the ways in which the terms “sustainability” and “ecology” have been uncritically adopted as the primary justification for the contributions that landscape architects make to the built environment. Certainly, landscape architecture is also a “projective” or imaginative discipline because it envisions the intersections among those realities in critical or challenging ways by making places that are unique, expressive, and experientially compelling.

Two recent developments have overshadowed these latter concerns. First, a turn in the profession that emphasizes “ecofriendly” or “green” design has resulted in a set of predictable responses to environmental sustainability, such as green roofs or constructed wetlands. The prominence of this utilitarian approach to function has eclipsed questions about how such approaches engage the equally relevant social, experiential, and symbolic functions of landscape. And second, academic discussions concerning “landscape urbanism” have gained traction among architects and landscape architects over the past decade. Its proponents claim that conjoining the terms “landscape” and “urbanism” frees landscape from being understood in counterpoint to the city (and attendant associations with remoteness, scenery, and nature). Hence, ecology is constructively understood as an overarching metaphor for interconnectivity: by recognizing that everything is bound together by the same dynamic processes, we see that our cities are as ecological as our landscapes, our landscapes as manufactured as our cities. Given this desire to leave behind binary divisions between city and landscape, center and periphery, or culture and nature, it is unfortunate that the rhetoric of landscape urbanism has been polarizing in other ways by arguing that landscape architecture should be liberated from its “traditional” concerns (the most commonly named are form, composition, and representation) by subsuming it under a different rubric and, presumably, by engaging in different modes of practice. Landscape urbanism’s call for a “disciplinary realignment” raises important pedagogical questions in terms of what ideas (theory, history, techniques) we teach and, significantly, what defines a discipline’s efficacy, if not its expertise. This has yet to be seriously addressed in pedagogical or methodological terms, which is why landscape urbanism as defined in the North American context is simply landscape architecture “rebranded.” Landscape architecture is already broadly cross-disciplinary in practice; it was founded as a profession by combining practical knowledge drawn from a constellation of other fields – geology, forestry, horticulture, and so on – and is influenced by visual culture, philosophy, science, politics, and poetry. It engages this collection of influences in order to propose or challenge how ever-changing social, economic, and technological conditions might be engaged and experienced on the ground. It is, in fact, the ground – its specific material, historical, and formal potential – that is missing from much of the conversation surrounding sustainability and landscape urbanism today. This account of Hargreaves Associates’ work is a consideration of alternative strategies that in their turn critique these recent developments.

Hargreaves Associates has been embroiled in the challenges of making public landscapes for almost thirty years. Its practice thus spans a time frame that has witnessed many changes both internal and external to the discipline. The aim of this book is to trace these shifts, utilizing Hargreaves Associates’ work as a vehicle in order to demonstrate how the utilitarian and infrastructural demands (hydrological, ecological, etc.) placed on landscapes can be engaged through vivid and precise design interventions rather than privileging one of these values at the expense of others. A second objective is to explicate the firm’s “geologic” design methodology, which incorporates diverse notions of strata – historical, material – to demonstrate its pertinence for dealing with the type of site conditions commonly encountered today, namely, the postindustrial landscape. Though landscape urbanism has, in the United States, been positioned as a response to the sprawling metropolis, which is characterized by a vast horizontal field that is automobile-dominated rather than by traditional definitions of city centers and building density, the sites vacated because of this horizontal expansion (old airports, industrial waterfronts) are exactly the types of locations that form the basis of projects most often referred to as exemplars of landscape urbanism, and they are the types of sites focused on in this book.

Given the prevalence of such sites today, we have entered a phase of park building that rivals the political momentum of the nineteenth century. This is an immense opportunity for landscape architects to engage in questions about the nature of public space, and the nature of “nature” as represented and constructed in urban landscapes, particularly because today’s site conditions are distinct from t hose of our predecessors. As George Hargreaves has said, the firm has never built on a greenfield site: there are no streams, no boulders, no forests, in other words, “no bones” on which to build its projects. Hargreaves Associates has taken advantage of of these conditions to develop methods to physically and conceptually build complexity back into sites that have been stripped of their ability to support diverse uses. Consequently, this book is organized into three chapters that address different notions of fabricated ground – geographies, techniques, and effects – and includes an examination of three projects within each theme. The choice of projects cited – by landscape standards quite modest in size, ranging from eighteen acres to two hundred acres – is to focus on the specificity of a “middle scale” of site.

The themed chapters are preceded by an introduction that situates Hargreaves Associates’ work with respect to the influences that were prevalent when Hargreaves began its practice. Given that earlier interpretations of the firm’s work are structured around terminology such as “process” and “open-endedness,” terms that have become more prevalent over the past two decades, the introduction traces how these ideas emerged with respect to that work. George Hargreaves and others have explained a shift in their approach as a move from a subjective engagement with process to a more intensive investigation of programming; however, this change is as much an indicator of the shifting nature and location of public park space and its funding as it is simply a reflection of the shifting intentions of the designer. Thus, the subsequent chapters include projects that span from the late 1980s to 2012 bringing into focus the consistent threads in Hargreaves Associates’ work that manifest differently in various projects, and that shift expression as externalities change.

The title of Chapter 1, “Geographies” signifies the intersecting cultural, natural, and political forces that influence a region’s transformation over time. I use the projects in this chapter as microcosms of these broader changes, and underscore the challenges that landscape architects face when transforming sites for public use, especially in regard to postindustrial sites. The notion of public, collective life is presented in two interrelated ways: first, in how sites are places of collective memory; and second, in the changing definition and role of who constitutes the public. The projects chosen for this category demonstrate how public space is about representation – of people, of place – whether or not we claim it to be so. The first project is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service (San Francisco’s Crissy Field), the second a state park (Los Angeles State Historic Park), and the third a downtown waterfront development (Chattanooga) that contains part of a National Trail – also a designation of the National Park Service. Consequently, these projects must address the needs of local residents while representing the aspirations for federal and state cultural landscapes.

The second chapter, “Techniques,” focuses on the relationship between technological and natural systems in order to demonstrate how the dynamic aspects of landscape are engaged via engineering and construction. The three projects in this chapter address water cleansing and control and are used to highlight the interface between landscape architecture and engineering. Guadalupe River Park illustrates the various, at times incompatible, definitions of “function” as it pertains to landscape, and demonstrates how different infrastructural systems can perform similarly in measurable ways without appearing identical. The other two projects, Sydney Olympic Park and Brightwater Wastewater Treatment Facility, are used to make a similar point by focusing on the inescapably aesthetic and ideological aspects of function.

The third thematic chapter, “Effects,” examines relationships among geometry, topography, and planting, and emphasizes the importance of form making to support a variety of conditions, experiences, and uses. The examples analyzed, Louisville Waterfront Park, the University of Cincinnati, and the Clinton Presidential Center Park, all use similar strategies for their organization. I discuss how form, material, and movement are orchestrated in the work, and how their various combinations constitute moments of awareness in the landscape where particular spatial or material attributes become legible. Working the earth to mold the ground is central to the landscape medium, and Hargreaves Associates’ facility in working with topography is fundamental to the effects of the work.

George Hargreaves received a bachelor of landscape architecture from the University of Georgia in 1977 and his master of landscape architecture from Harvard University in 1979 under Peter walker’s tenure as chair of the department. Hargreaves spent several years working at SWA, one of the incarnations of the collaboration between Hideo Sasaki and Peter Walker, before venturing out to form his own practice in 1983, initially named Hargreaves, Allen, Sinkosky & Loomis (HASL) and reincorporated as Hargreaves Associates in 1985. Hargreaves Associates office was first stationed in San Francisco, which remained their only location until Hargreaves became chair of the department of landscape architecture at Harvard University in 1996, at which time they opened their Cambridge, Massachusetts, office. After concluding his position as chair in 2003, Hargreaves opened a third location in New York City and, as of 2008, an office in London.

While George Hargreaves remains the design lead of Hargreaves Associates, the firm depends on the talents of other individuals, many of whom have been with the office for one or two decades. Of particular note are senior associate and president Mary Margaret Jones, who joined the firm in 1984 and has been instrumental in its direction, and former associate Glenn Allen, who was one of the founding partners of HASL.

Introduction

George Hargreaves and others who were educated in landscape architecture in the 1970s are situated at an interesting crossroads for the discipline. Characteristic of the time were Ian McHarg’s Seminal Manifesto.

Design with Nature (1969), along with Charles Jencks’s famous declaration that modernism ended at 3:32 P.M. on July 15, 1972 (referring to the destruction of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis). The period was marked by a call for an end to totalizing narratives of linear advancement while simultaneously offering the earth-ecosystem as a new totality. In response to this challenge, which landscape scholar Elizabeth Meyer has aptly named the “post-earth day conundrum,” designers sought to move beyond environmentalism and landscape architecture to involve challenges to hegemony – singularity, authority, hierarchy – in any form. Though the critique originated from within many disciplines across the arts and humanities, they shared a common goal of undermining what had become categorical impasses within their respective fields, such as medium specificity (art), singular authorship (literature, planning), and typology (architecture). In response to the array of emerging changes that typify this period, Hargreaves helped forge an approach within landscape architecture that expressed this broader shift in sensibility taking place.

As Hargreaves was venturing into practice in the early 1980s, critiques of modernist master planning and urban renewal were in full force. Critics such as Jane Jacobs (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 1961) had ushered in an era of community activism, which changed the relationship between designers and the community for whom they design, and challenged the divide between “public” and “expert.” Both grassroots environmentalism and federal regulation of pollution had taken a foothold, spurred on by publications such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962). This increased awareness eventually led to legislation pertaining to soil and water quality and thus affected the construction of landscapes, especially with regard to cleaning up the large swaths of toxic land in or adjacent to city centers and waterfronts. These sites – the so-called postindustrial landscape – still form the basis of much work that is happening in landscape architecture today and constitute the type of locales where Hargreaves Associates created its first important projects.

The 1970s-1980s was a period when the importance of history as a resource to be mined for design inspiration was reinvigorated as an idea. For some practices, history was invoked in the name of pluralism or populism, drawing on conventional icons or themes so that work could be “accessible” to a broad audience. This was especially visible in architecture, where historical references, represented in allegedly familiar signs and symbols, were celebrated (see the pleas by Charles Jencks, Robert Venturi, and Denise Scott Brown). In landscape architecture, history was invoked as a means to create specificity and uniqueness, especially on postindustrial sites, an early example being Seattle’s Gas Works Park (1971-88) by Richard Haag, where the relics of a gasification plant were preserved. By drawing on the past uses and materials of a particular place, landscape was conceptually understood as a cultural palimpsest – as one layer among many – rather than a tabular rasa, as had been the case during industrialization. Even on sites where all previous material traces (both natural and cultural) had been erased, history became a way to engage place as designers took inspiration from a site’s past (such as previous geometries or materials) to inform their designs. In this period the term “site specificity,” often used to describe Hargreaves Associates’ work, became a central concept. Rather than impose a unified or singular order, landscape architects engaged and produced complexity and variety by understanding sites in terms of processes occurring in time.

The impact of structuralism and poststructuralism infiltrated many disciplines at this moment and further expanded notions of context specificity. Structuralism, coming largely from the study of linguistics, sought to identify the underlying structures and codes that gave rise to the meaning of a work (such as how a novel is understood within a particular genre, and the history of the genre itself) in order to understand the full context of how a work signifies (rather than simply focusing on the particulars of a single work, such as the plot or narrative). Given that language itself was understood as a system apart from the physical world that it described, language was seen not as a reflection of the world, but as a construction of it. Poststructuralism furthered this argument by claiming that attempts to identify underlying structures would be no more likely to reveal the truer meaning of a work, because the means by which such structures are defined would themselves have embedded biases; therefore, there was no “deeper” understanding to be found. Rather, every work was produced, or reproduced, indefinitely, leading to the so-called decentering of knowledge. The dismantling of authoritative or truthful readings of texts brought about the “death of the author” and the birth of the “open work.” These developments challenged the notion that meaning is dependent on an author’s intent, arguing instead that meaning is based on the subjective interpretation of the reader, bringing to the fore questions about content (whether it can be embedded or inherent in a work), communication (what an audience can decipher about a work), and representation (who is speaking for whom).

The most direct influence of these methods on landscape architecture came by way of art criticism, in particular that of Rosalind Krauss. Krauss’s method of criticism opened up new ways of reading works, challenging what had been presumed to be key traits for understanding a work of art (originality, biography, genre, medium specificity, and so on). Her essay explicating the “expanded field” of sculpture utilized the work of many “earthworks” artists, and was structured around a set of terms that included “landscape” and “architecture.” This essay, as well as the artists she cited, was extremely influential in reinvigorating the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of the idea of “landscape” – the terms, methods, and representations around which site is constructed. As Hargreaves notes, the work of these artists appeared to him as “beacons on the parched field of designed landscapes,” influencing both his thinking and his formal language. All of this is to say that the redefinition and expansion of what constitutes context – cultural, historical, material, and disciplinary – became central in the production and evaluation of work.

Last, ecology began to be understood in an expansive, multipronged way. No longer referring only to the large-scale goals of resource conservation and regional planning, ecology was appealed to be a holistic theory of the environment, an enterprise that included human experience. Some critics and practitioners who sought to expand beyond the limits of positivist (McHargian) thinking placed emphasis on how an inclusive understanding of ecology could give rise to a new aesthetic for landscape and urban form. Many of these critics drew on the burgeoning field of environmental aesthetics and the work of social scientists such as Gregory Bateson (Steps to an Ecology of Mind, 1972) and philosophers such as Arnold Berleant. At this point in time (the late 1970s to the mid-1990s), questions of how new understandings of ecology could give rise to new landscapes were inseparable from questions of experience and aesthetics.

It is from within this rich constellation of ideas – transforming notions of public, site, context, and ecology – that Hargreaves ventured into practice. Hargreaves Associates’ early work, among that of several other practices at this time, marks an important moment in landscape architecture: one that bridged the divide that had dominated the discipline in the 1960s and 1970s, when the emphasis on large-scale planning led to a disregard for the qualitative and experiential aspects of landscape’s material and form.

So it is disappointing that we should again find ourselves with a recent but dominant trend focused on the pragmatic and operational aspects of landscape and dismissive of, or at least skeptical about, the more subjective and perceptual aspects of landscape. This trend has gained traction as systems theory (a way of looking at the web of interactions that constitute any organization, which cannot be understood by looking at the behavior of any one of its parts) and its associated terminology (self-organization, emergence, and complexity) has become a pervasive theoretical umbrella for design. One of the chief theorists of systems thinking, Fritjof Capra, argues that the theory of self-organizing systems is the broadest scientific formulation of the ecological paradigm. He describes the systems approach through five key shifts, which hold for natural and social sciences and the humanities: the shift from part to whole, from structure to process, from objective to “epistemic” science, from “building” to “network” as a metaphor for knowledge, and from truth to approximate descriptions. Though systems theory has been widespread in philosophy and science since the middle of the twentieth century, the paradigm shifted from viewing ecosystems as closed systems (balance, stasis) to understanding them as open to constant fluctuation (emergence, disturbance) did not occur until the 1980s, further contributing to our understanding of ecology as a metaphor for the mutability of all things, and marking a philosophical shift from being to becoming.

The ecological turn has influenced design in a multitude of ways, making it difficult to untangle the divergent ideologies at play when one evokes design in the name of “ecology.” For some, ecology maintains its conventional meaning and is used in design to refer to ecosystem health; its applicability is to planning large sites for habitat creation and protection. For others, it is used to generate novel form. The latter, often abetted by digital technology and software, has led to wide-ranging expressions, such as biomorphology (formal resemblance between human-made structures and natural structures), topology (spatial continuity achieved using parametric software), emergent material (also known as ecological succession, where changes in the composition of the landscape occur in somewhat predictable ways; an approach most prominent in landscape architecture). In all cases, the ecological influence in design can be broadly viewed through the lens of process, where processes are the forces that shape form.

An emphasis on process (formation) over product (form) was already broadly espoused in art practices in the 1970s and was issued as a challenge to the autonomy of the art object and conventional pictorial codes. Because Hargreaves took inspiration from “process” artists, such as Robert Smithson and Richard Serra, his work has been described as process driven and, as a result, could be seen as an antecedent to the widespread interest in emergence outlined above. This is no doubt because Hargreaves himself said that he was approaching “landscape as more open-ended, allowing the natural processes to somehow complete the project.” Since he made this statement two decades ago, there has been a further conflation of landscape and process, along with references to the emancipating or liberating effects of landscape as a metaphor for change. As already noted, emergence not only pertains to our understanding of ecosystems but includes the notion that social systems and places, like natural systems, evolve in unforeseen ways and consequently thwart our ability to plan them with any definitive ends in mind. In this view, ecology (nature) is the preeminent open work.

The fact that sites and systems are fundamentally open to change – their uses, meanings, and materials continually evolving – has led to a deemphasis on form (seen as too fixed) and experience (seen as too subjective) and, in some cases, resulted in dubious correlations among nature, landscape, and liberty. The presumption is that landscapes will naturally evolve to be more complex and more diverse, both physically and culturally, than at their inception. The systems view and its affiliated terminology of self-organization and emergence has been interpreted in such a way as to equate lack of “product” with open-endedness, the belief being that “by avoiding intricate compositional designs and precise planting arrangements [projects can] respond to future programmatic and political changes.” This notion has become increasingly widespread and has even been used in reference to Hargreaves Associates’ work. For example, landscape architect Martha Schwartz describes process-driven landscape design as catering to a “new naturalism,” and uses a project by Hargreaves Associates to illustrate this point. While she is right to criticize this sentiment, Hargreaves Associates’ work does not fit this description. Though Hargreaves may have inadvertently ushered in the emphasis on process over “product,” it was to inspire new formal, spatial, and experiential effects, not to eschew them.

Accordingly, this introduction seeks to distance Hargreaves Associates’ work from characterizations that equate process with lack of specificity in order to place questions of form and intent within the design of public space itself, rather than to displace them as the inevitable outcome of ongoing cultural and natural transformation, which is inherent in any project. In contrast to Hargreaves’s early statement that emphasized process, he has more recently said that he is “more interested in the geologic than the biologic,” since the organic is reminiscent of conventional ideas about nature. This recalls a sentiment expressed by Robert Smithson: “I do have a stronger tendency towards the inorganic than to the organic. The organic is closer to the idea of nature: I’m more interested in denaturalization or in artifice than I am in any kind of naturalism.” This distinction between the geologic and the biologic-ecologic provides a useful framework for discussing Hargreaves Associates’ work. This is not meant to neglect the importance of the health of natural systems (what we can learn from the science of ecology), but rather to consider the ways in which different scientific analogues, such as emergence and complexity, influence design methodology and expression. As part of such consideration, the characterization of Hargreaves Associates’ work outlined below interprets the firm’s work through a geological analogue in order to emphasize several things. First, the site in a geologic approach foregrounds the subsurface in terms of history, traces, and excavation. Second, the material of this approach emphasizes striation, as opposed to smoothness. In other words, the work is heterogeneous, characterized by distinct adjacencies or fissures between and among various forms and materials rather than subtle, even, or gradual transitions. And third, the form of a geologic approach utilizes prominent earthwork as a fundamental characteristic.